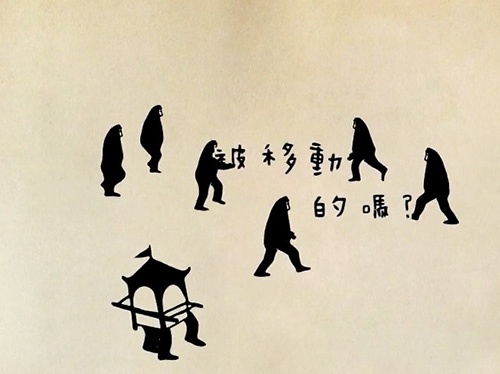

WAS BEING MOVED?; Ye Mimi; TRT: 11.00

About the state of moving and being moved: When people build a boat to carry themselves; when people start to walk backwards; when gods lead people to step on the Earth… Is it possible that everyone becomes someone else’s “far-afar” in the continuous movement?

Can you tell us about the source material of the Mazu pilgrimage and the boat builder?

The Baishatun Mazu pilgrimage is a very unique Taoist activity in Taiwan. The pilgrimage, itself, is a miracle. The sculpture of the Baishatun Mazu leads the pilgrims alone their route by shaking her sedan in the direction she wants to lead the pilgrimage. The pilgrimage usually lasts for eight to ten days. Thousands of people follow Mazu more than 400 kilometers from northern Taiwan to the middle of the country and back again.

The handmade wooden sailboat was made by two Chicago artists: James Barry and Hui-Min Tsen. The boat is part of their art project “The Mt. Baldy Expedition,” which is an interdisciplinary project that explores the act of commonplace exploration and the experience of wonder in daily life. After filming their boat, I went to Lanyu, a small island off the coast of Taiwan, to film another handmade wooden boat. The Lanyu boat is a ten man traditional boat made by the Taiwan native peoples for catching flying fish during the spring fishing season. I try to create a conversation between the sailboat and fishing boat.

The main connection between these source materials is the concept of “move” and “being moved.” Are people moving by themselves or moved by the Mazu? Do the boat builders move the boats, or do the boats move them? There may be many other connections, but I would like to leave those to the audience.

Can you tell us about calling your film “poetry film”?

I was first introduced to the term “poetry film” through watching a screening of the Zebra Poetry Film Festival. As a poet, I knew right away that’s the kind of video work I would like to make. In 2007, I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to study filmmaking and to continue experimenting with the relationship between poetry and film. Becoming a filmmaker doesn’t prevent me from being a poet. Instead, my poems grow with my films simultaneously. It’s like directing a group of electric jellyfish sneaking into a tilt tower to rub together.

Please tell us about your creative process.

Making a poetry film is like weaving. I always write something first before I go out to collect images, but everything is still unclear and improvised when I am shooting. At the editing stage, I like to collage the images. Afterwards, I write something based on the images and then collage the images more. In other words, my images and text feed each other instead of eating each other. They could become a sunny day, a fever, a humming song, or a glass of Bloody Mary, which, I never know.